A bill that passed the General Assembly with bipartisan support on Sunday would make Illinois the first state to prohibit officers from lying when interrogating those under 18.

Illinois would become the first state to bar the police from using deceptive tactics when interrogating young people under legislation that passed the General Assembly with near-unanimous support from Republicans and Democrats on Sunday.

The bill, which is headed to Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s desk, is intended to stop the police from lying during interrogations, a technique that is legal but that the bill’s supporters say often leads to false confessions.

The legislation gained momentum after what one supporter called a drumbeat of false confessions involving young people in recent years, both in Illinois and nationwide.

It would make Illinois the first state to prohibit law enforcement officers from knowingly communicating false facts about evidence — like claiming to have found a young person’s fingerprints on a gun — or making unauthorized promises about leniency when interrogating people under 18, according to the Innocence Project. Any confession in which a police officer “knowingly engages in deception” with a person under 18 would be presumed to be inadmissible in court under the bill.

While the bill provides a check on police deception, it does not include specific punishments for officers who lie in the interrogation room, said Stephanie Kollmann, policy director of the Children and Family Justice Center at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. It does not address police deception in other contexts, such as when a young person is stopped on the street or in school, and it might even incentivize officers to interrogate young people in those settings, Ms. Kollmann said.

False confessions have played a role in about 30 percent of all wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence, and recent studies suggest that people under 18 are two to three times more likely to falsely confess than adults, according to the Innocence Project.

In Illinois alone in the last three decades, there have been 100 wrongful convictions predicated on false confessions, including 31 involving people under 18, according to the Innocence Project.

Similar bills have been introduced in New York and Oregon, and supporters hope its passage in Illinois — by a vote of 114 to 0 in the House and 47 to 1 in the Senate — will lead to national movement on the issue. It was supported not only by groups that advocate for the wrongfully convicted but also by the Illinois Chiefs of Police and the Illinois State’s Attorney Association, according to the Innocence Project.

The office of Mr. Pritzker, a Democrat, did not respond to emails about the bill on Monday. State Representative Jim Durkin, a former prosecutor who is the Republican leader of the Illinois House, was among its sponsors and vocal supporters.

“Our criminal justice system should not be guided by a conviction, but rather it should be guided by the advancement of the truth,” Mr. Durkin said in a statement. “Deception can never be utilized under any condition in our criminal justice system and particularly against juveniles.”

State Senator Robert Peters, a Chicago Democrat who sponsored the bill, said in a statement that a disproportionate number of wrongful convictions had involved young Black people who had been convicted after the Chicago Police lied to them during questioning. He called Chicago “the wrongful conviction capital of the nation.”

One of several cases cited by the bill’s supporters involved four men — Charles Johnson, Larod Styles, LaShawn Ezell and Troshawn McCoy — who had been arrested as teenagers and spent more than 20 years behind bars for a 1995 double murder in Chicago.

A judge set aside their convictions in 2017 after prosecutors cited new evidence in the case. Lawyers for the men have said their confessions were coerced by the Chicago Police, who fed them information about the crime and then threatened them if they did not repeat the officers’ fabricated statements. The teenagers were told, according to their lawyers, that they might never see their families again, could serve life in prison or could even receive the death penalty.

“The history of false confessions in Illinois can never be erased, but this legislation is a critical step to ensuring that history is never repeated,” Kimberly M. Foxx, the Cook County state’s attorney, said in a statement. “I hope this is a start to rebuilding confidence and trust in a system that has done harm to so many people for far too long.”

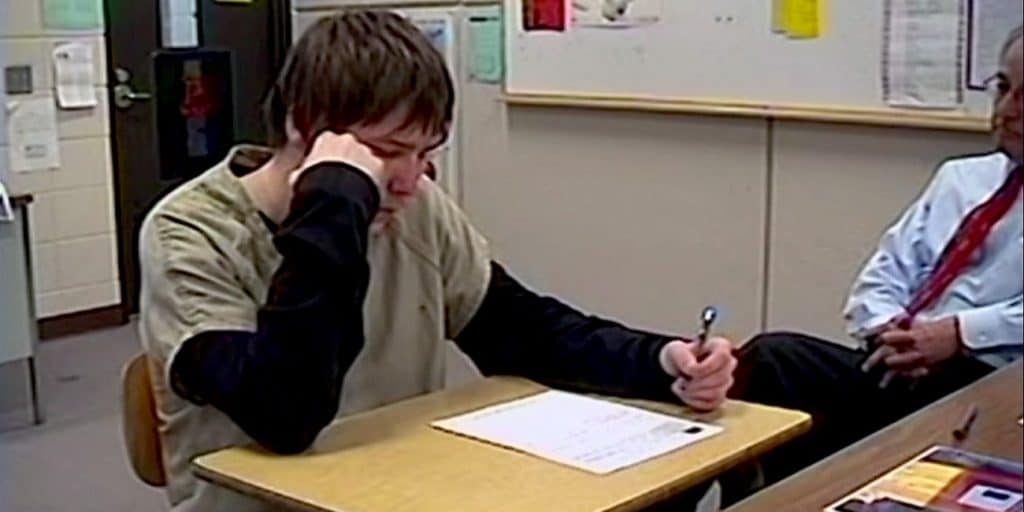

The case of Brendan Dassey, whose murder conviction was documented in the Netflix series “Making a Murderer,” drew national attention to the issue.

Mr. Dassey was 17 in 2007 when he was convicted of helping his uncle murder and sexually assault a photographer. Mr. Dassey has intellectual disabilities, and his legal team has long argued that his confession was coerced in a deeply flawed interrogation. In 2019, Gov. Tony Evers of Wisconsin denied a request to grant Mr. Dassey clemency.

“When a kid is in a stuffy interrogation room being grilled by adults, they’re scared and are more likely to say whatever it is they think the officer wants to hear to get themselves out of that situation, regardless of the truth,” Mr. Peters, the state senator, said in the statement.

“Police officers too often exploit this situation in an effort to elicit false information and statements from minors in order to help them with a case,” Mr. Peters said. “Real safety and justice can never be realized if we allow this practice to continue.”