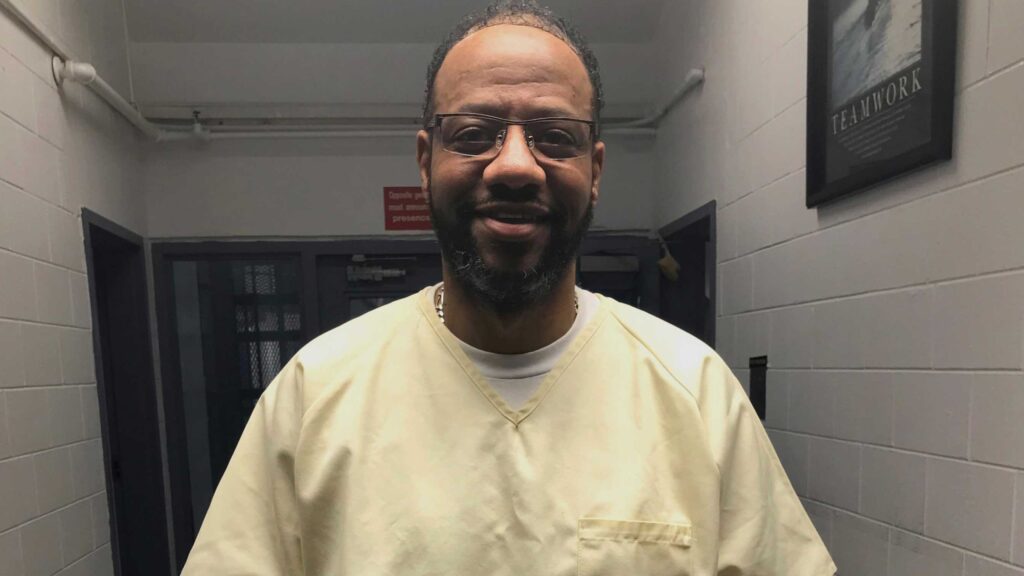

Pervis Payne lives with an intellectual disability and is scheduled to be executed in Tennessee on Dec. 3.

Pervis Payne, who has an intellectual disability, has spent 32 years facing execution because he stumbled upon what he described in court as “the worst thing I ever saw in my life.” And this December, he may be killed because he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Recently, Payne’s legal team discovered evidence that had been hidden by the State of Tennessee. DNA testing of this evidence could prove that Payne has been telling the truth all along — he didn’t commit the crime for which he’s been sentenced to death. That’s why the Innocence Project joined Henry and the Milbank firm in filing a legal petition for DNA testing in Payne’s case on July 22.

On June 27, 1987, Payne was waiting for his girlfriend at her apartment in Millington, Tennessee, when he saw a man with blood on him sprinting out of the building. The man ran past him, dropping change and papers as he ran, a few of which Payne picked up before he entered the building and made his way to his girlfriend’s apartment. There, he noticed that the door to the apartment across the hall was open and heard a noise.

Payne entered the neighbor’s apartment where he encountered Charisse Christopher, who had been stabbed 41 times and still had a knife in her throat.

The panicked 20-year-old tried to help. He noticed that Christopher’s hand was grasping at the knife, and removed it. Then he checked on her two young children before running to get help. Shortly after leaving the apartment, he saw police officers arriving. And for the second time that day, Payne was overcome with panic.

“Some other feeling just went all over me and just panicked, just like, oh, look at this,” Payne said in his testimony. “I’m coming out of here with blood on me and everything. It going to look like I done this crime.”

Payne was arrested later that day — the first misstep in the path that led to his wrongful conviction for the murder of Christopher and her 2-year-old daughter.

Who is Pervis Payne?

Payne grew up in Tipton County, Tennessee — once the third-largest cotton-producing county in the state — with parents who were both descendants of sharecropping families in the Jim Crow South. He is a loving son and brother and shared a tight bond with his sisters for whom he was always a source of fun and entertainment.

Payne lives with an intellectual disability and struggled in school. Though he tried, he continued to have difficulty with reading, spelling, and math, even after being placed in resource classes. Despite his best efforts, Payne was unable to graduate. Growing up he also had trouble with everyday tasks like cooking and doing laundry — as a child, he needed help feeding himself until he was 5.

Doctors have since confirmed through testing that Payne has an intellectual disability. Under the 8th Amendment, it would be unconstitutional to execute him.

Payne found it difficult to follow complicated instructions, which at times made it difficult for him to find work, but he was known for helping out around his father’s church in any way he could. He also worked with his father at his painting business, where he kept an eye out for his son.

Under the 8th Amendment, it would be unconstitutional to execute him.

But more than anything, Payne loved to make his mother and sisters laugh. But while wrongly incarcerated, he has missed out on more than three decades of laughter with his family, and was not able to be with them when his mother Bernice and sister Tyrasha died because he is serving a death sentence for a crime he didn’t commit.

The role of racial bias in Pervis Payne’s wrongful conviction

It wasn’t just his being in the wrong place at the wrong time that led to Payne’s wrongful conviction. The prosecution’s case against him exploited his intellectual disability, hid evidence, and relied on racist stereotypes of Black men to paint a portrait of Payne as a dangerous and hypersexualized drug user.

Payne didn’t know Christopher and had no reason to attack her. And no evidence suggested that he sexually assaulted her. Yet police and prosecutors argued that Payne had made an advance on Christopher while using drugs and alcohol and that, when she rejected him, he had stabbed her to death.

However, there was no evidence that Payne was using drugs. Payne was never given a drug test, though his mother begged police officers to perform one, and no evidence of drug use was reported during the initial investigation. Payne had no history of drug use or violence, and did not have a criminal record — or any contact with the legal system before the day he found Christopher in her apartment. But the prosecution argued that Payne had been searching for sex after using drugs and looking at a Playboy magazine.

This argument — that a young Black man became violent as a result of uncontrollable sexual urges and drug use — relied on harmful and false stereotypes of Black men, not the facts and evidence of the case.

Racial bias not only influenced the prosecution’s case, but also played a role in Payne’s sentencing.

Innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than innocent white people.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than innocent white people. And studies have found that the race of a victim influences the likelihood of the accused being given the death penalty. Nearly 300 Black people accused of murdering white people have been executed since 1976 — approximately 14 times more than the number of white people who were executed for murdering white people — according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Shelby County, where the trial took place, is among the 25 counties with the most recorded lynchings between 1877 and 1950, the Equal Justice Initiative reported. Payne grew up hearing stories of white men torturing and murdering Black men in the area. It is in the context of this history that the prosecution repeatedly referred to the victim’s “white skin” when pointing out areas of her body during Payne’s trial. The repeated reminder of Christopher’s whiteness, set against the backdrop of the county’s history of systemic racism, reinforced the negative stereotypes about Black men that the prosecution used to portray Payne as a killer.

The hidden evidence that could prove Pervis Payne’s innocence

Payne was wrongly convicted in February 1988, but it wasn’t until last December, as part of Kelley Henry’s team at the Federal Public Defender’s Office in Nashville’s re-investigation into his case, that previously hidden evidence was discovered: a bloodied comforter, sheets, and pillow.

This newly discovered evidence contains significant DNA material which could prove Payne’s innocence. Before this evidence was found, Payne had previously filed a request to test biological evidence in 2006 and was denied. Since then, laws in Tennessee have changed and now allow DNA evidence to be tested against existing databases. Payne has a right to test all of the evidence in his case.

Payne previously filed a request to test biological evidence in 2006 and was denied.

The bloodstained bedding, which came from the victims’ bedroom, also raises further questions about the case, as the prosecution had previously said that the crime occurred in and was contained to the kitchen.

The fight for justice continues

The Innocence Project has joined Henry and the Milbank firm in filing a request for DNA testing in Payne’s case.

Payne’s family has steadfastly fought for justice all these years and his father, who now has Parkinson’s disease, continues to travel to see his son as frequently as possible. Here’s how you can join the fight:

Sign this petition — show your support for Payne’s case and send him a note that you’ll fight for him.

Say his name and share his story on Twitter — make sure everyone knows about this injustice.